ANISHINABE

Raven Naramore

Ethnobotany Term Paper

5/3/11

The Seasonal Round: The Cultural Significance of Manoomin among the Anishinabe and the Cultural and Health Repercussions Associated with its Diminishment

Food represents the strongest connection we have to our culture second only to language. The foods that people recount as culturally significant occupy places in heart, mind and body. This multi-dimensional relationship to food is especially prevalent among subsistence cultures. The Anishinabe people from the White Earth Reservation maintain such a relationship to many foods found in their homelands along the lakes of Northern Minnesota and Wisconsin. Of vital importance to spiritual and physical well being is manoomin, wild rice. This paper seeks to examine the importance of manoomin in the spiritual, social and physical realms of Anishinabe culture and to investigate the effects of colonialism which caused the disruption of Anishinabe subsistence patterns. The eradication the land base, enforced sedentary settlement on reservations and disrupted the cultural transferral of subsistence knowledge through the boarding school system are the most pertinent factors.

For this paper I will privilege the term Anishinabe or Anishinaabeg to refer to the people who are also known as the Ojibway and Chippewa. Quotes will utilize all three terms to refer to the same people. Many Anishinabe words will also be used in the text with the English given immediately after. The use of Anishinabe terms serves to privilege their knowledge and de-center Western knowledge, and as such is an act of decolonization. Some of the activities described herein are still practiced today thus the use of some present tense verbs.

Homeland

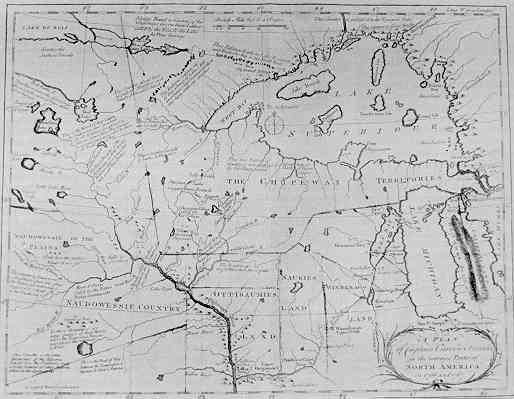

The Anishinabe were a seasonally migratory nation who, at the end of the 17th century, were firmly established in the northern parts of Wisconsin, Minnesota and southern Manitoba and Ontario. There are different bands of Anishinabe spread over a wide area who share language, foods and spiritual customs. They located to this territory from parts further east, displaced by the influence of European settlement and fur trade disputes. Their subsistence lifestyle followed a migratory pattern known as the Seasonal Round which honored the balance of nature and was synced with the provision of staple foods located in their Great Lakes homeland (Miller, 58).

The Seasonal Round

The Anishinabe Nation developed the Seasonal Round which describes annual work cycle of the Anishinaabeg. The seasonal migration pattern they followed according to the availabilityof foods throughout their homelands. This diversified subsistence pattern supported them, even when nature caused scarcity among one strand of their staple foods; venison, wild rice, fish, maple sugar, and corn. The round started with Iskigamizige-giizis the Sap Boiling Moon (Miller). After the long winter, the sugaring season was greatly anticipated; for the food it would bring and the socializing opportunity it afforded the people after long winter isolation. Waabigoni-giizis, the flowering moon, signaled the return of the sturgeon. During the 3-4 week spawning period, bands would gather at river mouths along the shores of Lake Superior. This was the largest gathering of the Anishinaabeg because the size of the fish harvest amply fed the people. Ode-imini-giizis, the Strawberry Moon, also known as Gitige-giizis, the Planting Moon brought the Anishinaabeg back to their summer villages for the planting season. The most important cultivated crops were corn, squash, beans and potatoes. Aabita-Niibino-giizis, Mid Summer Moon, also known as Miini-giizis, Blueberry Moon or Miskomini-giizis, Raspberry Moon, indicated that the berries were ripe and harvesting could begin. Blueberries, blackberries, raspberries, choke cherries, gooseberries, huckleberries, June berries, and pin cherries were/are some of fruits that were collected for both immediate consumption and preservation. At the end of summer came the Manoominikewi-Giizis, the wild rice moon. The Anishinabe relocated to rice camps along designated lakes for the wild rice harvest which represented the wealth of the Anishinabe. If the rice harvest was meager, there would be less trading with Europeans because families had to concentrate more time hunting for meat through winter. If harvests were plentiful, which they often were, the men could dedicate more time for fur hunting and the rice itself could be used as a trade item. This food stored well, and along with corn and maple sugar were vital food sources to the non-Anishinabe traders and trappers in the area (Miller 48-58). Adikomemi-giizis, White Fish Moon, was another important fishing period and catches were carefully dried for use through the long winter. Gashkadino-giizis, the Freezing Moon signaled the time of travel to their winter camps where the Anishinaabeg hunted and ice fished to supplement the summer’s bounty. Game animals sought were deer, bear, beaver, turkey, moose, rabbits, goose, and duck.

Manoomin Harvesting

The collecting of monoomin was a highly regulated, yet joyous social occasion and it was the last big gathering before the long winter isolation. The organization of the harvest was delicately administered by a Ricing Ogimaakewe, (Rice Chief), a person with the equivalent respect as a Peace Chief, and a council of advisors appointed by the Ogimaakewe (Vennum, 180). These leaders monitored the ricing grounds noting the ripening progression, policed the lakes to prevent early harvesters, administered fines for transgressions, announced the times of harvesting and had the authority to call off harvesting due to dangerous weather. Families would move to their ricing camps from their summer villages between August and September, depending on where their ricing grounds were located (Meyer 26-27) . The Ricing Ogimaakewe, who was chosen by each village, would divide the ricing grounds among the families and women from each household would travel to their selected spots and tie up the rice sheaves marking their claim and supporting the manoomin as it matured. When the manoomin was ripe the Rice Chief would announce that harvesting could begin. Then an elder would go out and collect some manoomin bring it back for processing and eating before the harvesting could begin in ernest (Vennum, 171). Ricing teams would work in twos or threes with a man usually poling the canoes and women gently shaking or knocking the manoomin between two sticks to dislodge the ripe kernels. Several passes were made over each spot to gather the later ripening manoomin. Processing the manoomin was done on shore first by dry roasting, then pounding to remove the husks and winnowing to remove the chaff.

The mood during the ricing time is light and jovial, and at its mention today fond memories are recollected from years past. “Despite the hard work, the harvest was a period of social gatherings, joking and horseplay, storytelling, romance, exchange of news, dancing and games (Vennum, 188).” The whole community, including the children contributed to the work. The inclusion of children in harvesting work transferred essential subsistence knowledge and conferred among the younger generation their identity within the community. These activities offer a valuable opportunity for children to develop their own sense of value and power and to connect themselves to the group. The camps were not just work places they are also places of romance and gaming.

The manoomin stands also offered convenient cover for romantic encounters among the high manoomin grasses where lovers would set up a bird call signals to communicate with each other out of eye sight. Slow times on the water were filled with communal singing with the canoe sides used as a drum, flute playing and other handwork. Music continued at the camps when singers would create the rhythm for the pounders and stampers. Stamping the rice or dancing the manoomin, which released the husks, afforded young people a way of courting. A young girl would bring her sweetheart beaded moccasins and ask him to dance the rice for her. Back at the camps lacrosse games were held between the villages for the men and both females and males took part in canoe races. Nights were filled with music and the Women’s Dance, which was a coupled circle dance in which the partners exchanged gifts. If there wasn’t a dance the moccasin game, the Anishinabe game of chance, was played where one team hid something under a moccasin and the other team had to guess where it was hidden all done to the accompaniment of special songs (192-193). Music, song sharing and learning were important cultural components of harvest time, this along with all the other activities of the harvest conveyed what it meant to be Anishinabe. Ernie Landgren of Nett Lake said “There’s a feeling you get out there that’s hard to get other places. You’re close to Mother Nature, seeing things grow and harvesting the results of the water and sun and winds. . . We sort of touch our roots when we’re among the rice plants (195)”

Manoomin: Food from the Gichi-Manidoo (Great Sprit) so the Anishinabe can Live

The essential nature of staple foods to Anishinabe culture is evidenced in the names of the months of the year. These connections are also strengthened in the origin stories of the foods and the cultural protocols associated with its collection, eating and use as ceremonial offering. Thomas Vennum writes in his expansive work, Wild Rice and the Ojibway People, “Traditional Ojibway life elevates rice above being food simply for consumption or barter. Stories and legends. . . , show the centrality of wild rice to Ojibway culture. . . [It] approached the status of a sacred food (Vennum 58).” Wild rice, Zizania aquatic, comes to the Anishinabe through their culture hero Wenabozho, who is also the creator of the earth and the Midewiwin (medicine lodge). “The Ojibway incorporated into the cycle of Wenabozhoo stores their most deeply held religious beliefs, ethical codes of conduct and explanations for natural phenomena (61).

The most important aspects of Anishinabe culture, the ability to be nurtured and healed, come from Wenabozhoo which signifies the importance of manoomin. Wenabozhoo was told by his grandmother to begin his puberty ritual in which he was sent into the forest to fast, pray and seek his spiritual helpers. Manoomin appears to him as his vision and he is struck by its beauty. He returns to tell his grandmother who returns with him to collect the seed which they sow in another lake. Wenabozhoo returns to his journey in which some bushes tell him to eat their roots. He does and falls sick; there is a taboo against eating during the vision quest. He recovers and is again tempted but resists but then sees manoomin growing in the river and recalls that it is the plant that he collected seeds from already and he eats it and is nourished by it. By challenging the taboo, he gains the manoomin as a staple food for the people (61-62). It is believed that the Gichi-Manidoo gave manoomin to the Anishinabe as their food, so that they may live.

To show gratitude and respect for the gift of manoomin there are many ceremonies that include the food as a sacred offering. After the manoomin harvest a feast of thanksgiving was held and offerings of the new rice were made to the spirits. The Anishinabe believed that future harvest would not ripen if they did not make the offering. This belief affirms that minoomin was a gift from the creator and could be taken away. The woman who called for the feast would offer tobacco, talk to the thunderbirds and the sun before anyone was allowed to eat. At the thanksgiving feast for maple sugar a big pot of rice was cooked with sugar which was offered to the Gichi-Manidoo before being served to the guests. During the fall midewiwin (medicine) ceremonies were held which aided the ripening of the harvest. The anthropologist Eva Lips who did field work among the Nett Lake Reservation in Minnesota in 1947 writes, “The rice harvest of the Ojibway is not just an event with temporal boundaries of weeks. . .it is the decisive event of the year, of the total economic life and with it, life itself (72).” At the Drum Dance ceremony green rice was blown to each of the directions and to the Gichi-Manidoo as late as 1966 (73). Taboos surrounding the manoomin further indicate the elemental importance of this food from the Gichi-Manidoo. Menstruating women were not allowed to collect manoomin, or bathe in the waters in which it was growing. Mourners were not allowed to take part of the harvest or eat from the new harvest before being hand fed the new crop by a member of their family. Rice was offered at the naming ceremonies of babies and included in the burials of the dead. The presence of manoomin followed the Anishinabe from birth to death and at every important milestone in between (78-79).

The reverence that Anishinaabeg place on manoomin as a food source is well founded due to its high nutritional value. Manoomin possess higher protein content then that of actual rice, oat flour or corn meal and possesses many vitamins and minerals.

The protein content of wild rice is relatively high for a cereal and it contains more lysine and methionine than most common cereals. Wild rice is a good source of the B vitamins-thiamine, riboflavin, andniacin-and contains common minerals in amounts comparable to those in oats, wheat, and corn. (Anderson 954)

Manoomin was prepared in a myriad of dishes both sweet and savory. During sugaring, manoomin was cooked with maple sugar and dried berries for a sweet pudding. It was commonly added to meat stews containing any number of meats and vegetables. Mothers weaned their babies on meat broth mixed with manoomin. Manoomin can be pounded into a flour to make a kind of bread. The chaff, considered a delicacy, was also collected and added to soups as a thickener. Manoomin was cooked in water with animal fat to impart flavor. A special dish of fish, corn and wild rice was boiled in water till thick and rich (35-54). Manoomin flavored water fowl that fed on the grains was one of the food highlights of the harvest. Ducks, geese, rails and teals would become so heavy with rice that they would be sluggish in taking flight and were easily caught by ricers in canoes. “Jenks noted that the waterfowl, far from damaging the wild rice crop were really gleaners and picked up and preserved in the most delicious way the grain which otherwise the Indian would have lost completely (56).

All residents of the Great Lakes regions knew of the value of manoomin whom it supported especially in times when other food sources were scarce. It was a highly valued commodity and could be used in place of money to pay fines doled out by village leaders, to pay for healing ceremonies to medicine people and as a currency for trade items (180). The presence of manoomin as a food source afforded the Anishinabe the luxury of time to pursue game animals for the fur trade, whose meat was not prized. The traders relied heavily on this staple crop for their own survival and in years when the rice harvest failed they suffered not only from food shortages, but also in trade business. The manoomin sustained the trading industry which contributed to the settlement of the area by non-Indigenous people, which had disastrous effects on the Anishinabe.

Loggers, Traders and Treaties

The expansion of the capitalist economy of the colonizers brought a large influx of white settlers to Anishinabe homelands. The demand for agricultural cash crops intensified the desire for Anishinabe land and the drop in the beaver population required fur traders to diversify their industry into lumber and mining. The first large land cession, known as the St. Peter’s Treaty, occurred in 1837, which ceded portions of Minnesota and Wisconsin. Even though lands had technically been “sold” to the US, the Anishinabe continued to hold usufruct rights and the Seasonal Round continued. The discovery of copper and iron on the north shore of Gichigami (Lake Superior) spurred the US government into the creation of a reserve for the some bands of Anishinabe by the Treaty of La Pointe in 1854 (Miller, 37). The Anishinabe usufruct rights were now being compromised by the large influx of settlers to the area. The ceded lands were being logged, mined, and farmed by whites that altered the landscape. Settlers set up whisky salons in the mining camps, and brought venereal disease and small pox to the Anishinabe. In 1867 the Mississippi Band leaders, in an effort to limit contact with whites, agreed to a treaty which removed them to the White Earth Reservation. Present in the document is the assimilationist language that aimed to replace Anishinabe culture with European culture by encouraging agricultural pursuits (Kappler Article 3 & 6). The US, under pressure from resource extractors, wanted to consolidate the Anishinabe on their land to open up parts of the reserve to logging. Many other poorer bands were relocated to the White Earth Reservation causing a population spike and a land squeeze. Subsistence cultures require large expanses of land for support. The concentration of many different bands on White Earth could not provide for the needs of everyone. Sugar bush stands, manoomin fields, and berry grounds were now coveted by many more people then it could sustain. The damming of rivers for the logging industry changed the water levels in many lakes and decimated the manoomin harvest. The Anishinabe could no longer seasonally migrate to accommodate their needs. Instead they were stuck on the reservation and were left to food provided by both logging moguls and the US government.

Rations

By the early1900’s food rations from the US government provided a substantial percentage of the Anishinabe food resources. In exchange for the food rich lands ceded to the US, the Anishinaabeg received flour, beef, beans, bacon, sugar, lard, coffee and tobacco (Kopp). The rations were initially intended as temporary emergency measures until which time the Anishinaabeg would become proficient farmers. Although some Anishinabe continued to follow the Seasonal Round and some even became famers, many people did not posses land suitable for farming, or had lost their land in the allotment fiasco where individual allotments were sold and “surplus” land left over after every qualifying male head of household had received their parcel was sold to white settlers. The result led the commissioner of Indian Affairs, W. A. Jones, to write in 1900, “To confine a people to reservations where the natural conditions are such that agriculture is more or less a failure and all other means of making a livelihood limited and uncertain, it follows inevitably that they must be fed wholly or in part by some outside source, or drop out of existence (Berzok 33). This food dependency meant that the Anishinabe were in part at the mercy of the Indian agents in charge of distributing rations, who would often withhold rations in order force cooperation. Dependency also meant eating foods which had no cultural relevance, and was/is inferior in nutritional quality to the traditional foods which were adapted to their bodies’ digestive and immune systems (Nabhan). The change in diet from Indigenous foods to Westernized foods represents one of the most drastic dietary changes in history; changes whose effects are being severely felt among Indigenous people everywhere.

Nutritional Ecogenetics

Nutritional Ecogenetics is the study of the interaction between nutritional elements of a particular environment with human genetics (Health Dictionary). Plants possess secondary compounds which aid them in a myriad of ways. Some of these secondary compounds can actually turn on and off genetic traits within humans. Here is an example; fava beans and fava bean pollen illicit Baghdad fever in male populations in malarial zones around the world. Although the sickness is an inconvenience it confers upon the sufferer increased resistance to malaria (Nabhan, 63). These interactions are either labeled disorders or adaptations depending on whether or not they are helping or hurting an individual in a current set of environmental parameters. Take for example the Tohono O’odham of southern Arizona; the desert plants have a myriad of ways that they protect themselves from drought. The prickly pear contains mucilage which slows moisture loss. When eaten this fruit slows the glucose release during digestion ensuring proper insulin regulation, thus prickly pear consumption offered protection against diabetes. The Tohono O’odham adapted to the slow glucose released foods of the desert and while they were eating desert foods, this adaptation aided their health. Once the Tohono O’odham diet changed to eating fast release foods, this adaptation became a disorder because their bodies do not process glucose fast enough to avoid the dumping of sugar into the blood stream which contributes to diabetes.

Diseases, plants and humans co-evolve rendering unique genetic variations among people of different environmental determinates. These adaptations usually offer advantageous traits for a given group of people in response to environmental threats like malaria or diabetes (Nabhan). The disruption in Indigenous lifestyle imposed by colonialism and reservation life exposed them to new foods, parasites, diseases and stresses, many of which their genes were not pre-adapted to deal with. The resiliency of Indigenous people has been thoroughly compromised by the dramatic shift in their diet and lifestyle resulting in the obesity and diabetes epidemic among Indigenous people.

Diabetes

Thirty percent of all Indigenous people living on the White Earth Reservation have diabetes.

Diabetes is a disease that affects the way the body uses food. Normally, the body turns food into sugar for energy. Then, the blood carries this sugar to cells throughout the body. There, insulin, a hormone, helps turn sugar from food into energy for the body to work. But when you have diabetes, something goes wrong. The body makes little or no insulin or insulin can’t get blood sugar into the cells. As a result, the body doesn’t get the fuel it needs and blood sugar stays too high. (White Earth Reservation)

The diabetes rates among Indigenous Americans are over twice that of European Americans with the Tohono O’odham having the highest a rate of 50% (167-169). There has been continuous study of diabetes among Indigenous people in this country with some alarming conclusions. Diabetes as a debilitating disease was virtually unknown in the 1960’s. Adults showing elevated blood sugar rates did not develop the secondary symptoms of renal failure, decreased circulation leading to amputations and acidotic comas typical with prolonged diabetes.

As this first diabetic generation aged and did not achieve normal blood sugars as a result of diet and drug therapy, the expected secondary complications appeared. The conclusion accepted now is that in 1965 Indian diabetes had existed less than fifteen years and therefore a large enough group of adults had not been found who had diabetes of sufficient duration to result in complications. As mothers with high, uncontrolled blood sugars during pregnancy gave birth to the next generation, the children they gave birth to became obese at younger ages, were at higher risk for developing diabetes and developed this disease at a younger age then their parents. (Justice 49-50)

This pattern continues through the generations with younger people acquiring what used to be considered “adult onset” diabetes (Type 2) now developing the disease while children. The severity of secondary symtoms of diabetes increases in severity the longer a person has diabetes, doubling the mortality rate. Reduced life expectancy threatens the survival of an entire culture as children are orphaned early and life, middle aged adults require intensive medical care straining family resources, and the population of elders dwindles. Thankfully, this devastating trend can be reversed by eschewing Western, processed, nutritionally deficient food in favor of pre-reservation foods.

Pre-reservation foods are vastly superior in nutritional content then commodity foods. Researchers Calloway, Giauque and Costa concluded that,

the basis of the compositional data only, Arizona Indians appear to have a much better probability of meeting mineral needs from locally grown and traditionally prepared plant foods than from an isoenergetic amount of most of the commodities that have been given . . . Each substitution of milled and refined commodities for crude natural foods and traditionally prepared products must result in lowered mineral content of the Indian diet.

(Kopp 21-22)

The majority of traditional foods are fiber rich, slow release foods, where the sugar released in the food is digested at the same rate that insulin is produced to process it into energy. Anishinabe wisdom has always understood that their diet prior to European contact nourished them on several levels, kept them healthy, and free from disease. In Robert E. Ritzenthaler’s work Chippewa Preoccupation with Health: Change in a traditional Attitude Resulting from Modern Health Problems published in 1953 one Anishinabe elder said,

Well, a long time ago people didn’t get sick like they do now, you know. Sometimes I blame the food we eat now. Maybe it’s the food that does it. . . . See, the Indians all had their own land, they had [wild] potatoes, they had rice, they had maple sugar, they had deer meat, they had ducks-all these wild stuff, you know they eat. The never bought anything from canned stuff. And they fixed their food their own way. (Vennum, 55)

Winona Laduke, the respected Anishinabe community organizer and national environmentalist who lives on the White Earth Reservation, argues that food sovereignty is essential for the survival of the Anishinabe people. She writes that returning to Indigenous foods like hominy, Arikira squash and Pottawatomi lima beans can reduce the rates of diabetes and improve overall health. By localizing the food system and returning control over what Anishinaabeg eat to the Anishinabe, they improve diet, reduce food miles and increase local investment through the financial support of reservation based farms and food businesses. Food sovereignty restores culturally relevant food and food ways which sustain Anishinabe culture and preserves, uses and honors Anishinabe wisdom.

The gift of manoomin also represents a sacred covenant with Gichi-Manidoo. The cultural traditions, ceremonies, stories, songs and taboos associated with manoomin provide the essence of Anishinabe identity. Without a strong cultural identity the spirit of the people gets sick. In response to cultural deficiencies people turn to alcohol, drugs, violence and suicide. The collective trauma of assimilation in the boarding schools, where instead of learning how to be Anishinabe, children were taught to be white-something that they were not and could never be. They not only lost their connection to their Anishinabe life way, they were told it was heathen, wrong, savage and dying. The children became disconnected from the land, the food that sustained their people for generations and the vast wealth of knowledge associated with Anishinabe food ways. The harmony between the land and the people is disrupted, food, a sacred gift, now causes deadly health problems and threatens the survival of Anishinabe culture. Colonialism is not over for Indigenous people, it gets delivered to their homes in the form of commodities once a month.

Thankfully many people are bringing back the traditional foods and reestablishing a connection to land, culture and community. The White Earth Land Recovery Project promotes food sovereignty by supporting the harvest of manoomin, along with other traditional foods, and distributing it to reservation schools and to elders with diabetes. They include traditional food ways into the curriculum in schools and sponsor programs that create space for elders to share wisdom with the younger generation. There are now reservation farms offering employment in a place with a 30% unemployment rate (White Earth Reservation Facts and Figures). Native Harvest is a business which sells traditional foods through a website supporting the sugaring and manoomin harvest practice. They are working for food sovereignty; weaving Anishinabe wisdom into the diet, contemporary institutions and economies to put an end to colonialism so the people, as Anishinabe, may thrive.

1 Wild rice

2 Jonathan Carver’s 1769 map located on google images

All the Anishinabe month names come from WOJB website. 2010. Calendar Names page. Accessed on 5/3/11.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Anderson, R. A. "Wild Rice Nuritional Review." Cereal Chemistry (1975): 949-955.

Berzok, Linda Murray. American Indian Food. Westport: Green Wood Press, 2005.

Health Dictionary. Health Dictonary. 2005. 8 5 2011 <http://www.healthdictionary.info/Ecogenetics.htm>.

Justice, James W. "Twenty Years of Diabetes on teh Warm Springs Indian Reservation, Oregon." American Indian Culture and Research Journal (1989): 49-81.

Kappler, Andrew. "Treaty with the Chippewa 1854 and 1867." Inidan Affairs Laws and Treaties. 9 April 2011 <http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/index.htm>.

Kopp, Judy. "Cross Cultural Contacts: Changes in the Diet and Nutrition of Navajo Indians." American Indian Culture and Research Journal (1986): 1-30.

Laduke, Winona. "Anisninabe Prophecy: Communities must choose Green Path for Food, Energy." Tribal College (2008): 60-63.

Meyer, Melissa. The White Earth Tragedy. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994.

Miller, Cary. Omigaag. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010.

Nabhan, Gary. Why Some Like it Hot. Washington: Island Press, 2004.

Vennum, Thomas Jr. Wild Rice and the Ojibway People. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1988.

White Earth Reservation. Health: What is Diabetes. 8 May 2011 <http://www.whiteearth.com/programs/?page_id=370&program_id=4>.

Traditional Indigenous Foods

History of Traditional Tribal FoodsFoods Indigenous to the Western Hemisphere

Geographic Areas

Foods of CaliforniaFoods of Great Basin

Foods of Mexico

Foods of Northwest

Foods of Peru

Foods of Plains

Foods of Plateau

Foods of Southwest

Foods of Subarctic

Foods of Texas